100 great novels by living authors

The following is a list of 100 books by living authors that I have read and highly recommend. I wanted to put together a list of ‘modern classics’, and having the criterion of a living author is a way to impose some currency while at the same time allowing for a certain breadth. Of course, this leaves out plenty of great authors who have unfortunately passed on, whether recently (Chinua Achebe) or centuries ago (Laurence Sterne). I have another list for the dead authors and a list for graphic novels. Every now and then I get around to updating them.

Adair, Gilbert, A Closed Book

Gilbert Adair previously won the Scott-Moncrieff prize for his extraordinary translation of the late Georges Perec’s A Void–a novel composed without the letter “e”– and some of that author’s wit, allusiveness and self- conscious artistry find their way into Adair’s new book, transmuted into something altogether more sinister. This is a powerful psychological thriller, well-paced, energetic (and occasionally very funny) but it also incorporates some subtle philosophical and literary questions into its narrative: How far can we believe what we read (or hear) and how does a reader’s trust in a writer’s fictional world equate with the trust required in allowing someone to interpret the world for us? See for yourself. (Amazon.co.uk review)

Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi, Purple Hibiscus

Purple Hibiscus, Nigerian-born writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s debut, begins like many novels set in regions considered exotic by the western reader: the politics, climate, social customs, and, above all, food of Nigeria (balls of fufu rolled between the fingers, okpa bought from roadside vendors) unfold like the purple hibiscus of the title, rare and fascinating. But within a few pages, these details, however vividly rendered, melt into the background of a larger, more compelling story of a joyless family. Fifteen-year-old Kambili is the dutiful and self-effacing daughter of a rich man, a religious fanatic and domestic tyrant whose public image is of a politically courageous newspaper publisher and philanthropist. No one in Papa’s ancestral village, where he is titled “Omelora” (One Who Does For the Community), knows why Kambili’s brother cannot move one of his fingers, nor why her mother keeps losing her pregnancies. When a widowed aunt takes an interest in Kambili, her family begins to unravel and re-form itself in unpredictable ways. (Amazon.com review)

Amis, Martin, Time’s Arrow

Amis attempts here to write a path into and through the inverted morality of the Nazis: how can a writer tell about something that’s fundamentally unspeakable? Amis’ solution is a deft literary conceit of narrative inversion. He puts two separate consciousnesses into the person of one man, ex-Nazi doctor Tod T. Friendly. One identity wakes at the moment of Friendly’s death and runs backwards in time, like a movie played in reverse, (e.g., factory smokestacks scrub the air clean,) unaware of the terrible past he approaches. The “normal” consciousness runs in time’s regular direction, fleeing his ignominious history. (Amazon.com review)

Amsterdam, Steven K., Things We Didn’t See Coming

Given that its nine linked stories are set in a postapocalyptic near future, the pleasure of Amsterdam’s debut collection is surprising. Over the course of the book, just about every possible disaster assails the unidentified country in which the stories are set. Floods, drought, mob rule, and a virus that has one deranged character coughing up blood — each play a role in the disintegration of the world as we know it, and Amsterdam’s narrator survives them all, first as a thief, later as a bureaucrat (which turns out to be not much different from a thief), and finally as a 40-year-old, cancer-ridden tour guide. Among the high points are Dry Land, in which the narrator encounters a drunken mother and her daughter clinging to each other in a cataclysmic flood, though each is more likely to survive alone; and Cake Walk, with a narrator who hides in a tree while a man infected with a deadly virus destroys his campsite. Though a couple of the later stories lack polish and punch, Amsterdam’s varied catastrophes are vividly executed, while his resilient narrator’s travails are harrowing. (Publishers Weekly review)

Atkinson, Kate, Life After Life

What if you had the chance to live your life again and again, until you finally got it right? During a snowstorm in England in 1910, a baby is born and dies before she can take her first breath. During a snowstorm in England in 1910, the same baby is born and lives to tell the tale. What if there were second chances? And third chances? In fact an infinite number of chances to live your life? Would you eventually be able to save the world from its own inevitable destiny? And would you even want to? Life After Life follows Ursula Todd as she lives through the turbulent events of the last century again and again. With wit and compassion, Kate Atkinson finds warmth even in life’s bleakest moments, and shows an extraordinary ability to evoke the past. Here she is at her most profound and inventive, in a novel that celebrates the best and worst of ourselves. (Amazon.com review)

Atwood, Margaret, The Blind Assassin

The Blind Assassin is a tale of two sisters, one of whom dies under ambiguous circumstances in the opening pages. The survivor, Iris Chase Griffen, initially seems a little cold-blooded about this death in the family. But as Margaret Atwood’s most ambitious work unfolds–a tricky process, in fact, with several nested narratives and even an entire novel-within-a-novel–we’re reminded of just how complicated the familial game of hide-and-seek can be: “What had she been thinking of as the car sailed off the bridge, then hung suspended in the afternoon sunlight, glinting like a dragonfly, for that one instant of held breath before the plummet? Of Alex, of Richard, of bad faith, of our father and his wreckage; of God, perhaps, and her fatal, triangular bargain.” Meanwhile, Atwood immediately launches into an excerpt from Laura Chase’s novel, The Blind Assassin, posthumously published in 1947. In this double-decker concoction, a wealthy woman dabbles in blue-collar passion, even as her lover regales her with a series of science-fictional parables. Complicated? You bet. But the author puts all this variegation to good use, taking expert measure of our capacity for self-delusion and complicity, not to mention desolation. (Amazon.com review)

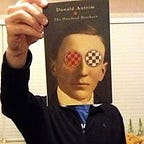

Auster, Paul, The New York Trilogy

The New York Trilogy is an astonishing and original book: three cleverly interconnected novels that exploit the elements of standard detective fiction and achieve a new genre that is all the more gripping for its starkness. In each story the search for clues leads to remarkable coincidences in the universe as the simple act of trailing a man ultimately becomes a startling investigation of what it means to be human. Auster’s book is modern fiction at its finest: bold, arresting and unputdownable. (Publisher’s description)

Barker, Nicola, Darkmans

There isn’t much plot to Barker’s Man Booker-shortlisted novel, but a cast of eccentric characters, a torrent of inventive prose and an irresistible synthesis of wickedly humorous and unsettlingly supernatural elements more than compensate for the loose itinerary. The novel is set in a contemporaneous British district bisected by the arrival of the Channel Tunnel’s international passenger station, a sore point for one of the central characters, cranky 61-year-old Daniel Beede, distraught at the loss of local landmarks. Beede is estranged from his prescription drug-dealing son Kane, though they share a flat, where Gaffar, a muscular Kurdish refugee with a rabid fear of salad greens, takes up residence. Beede is friends with Elen, a podiatrist, and with Isidore, Elen’s paranoid and narcoleptic husband; their young son Fleet is a spooky prodigy who, in one of this intricate tale’s several instances of mind-bending nuttiness, may actually be Isidore’s ancestor from nine generations ago. This improbable premise is supported by the boy’s propensity for quoting bits of the biography of King Edward IV’s court jester, one John Scogin, the dark man who haunts the book. Despite the story’s plotless sprawl, any reader open to the appeal of an ambitious author’s kaleidoscopic imagination will relish this bravura accomplishment. (Publishers Weekly review)

Barker, Pat, The Regeneration Trilogy

Pat Barker’s work never makes comfortable reading, for she chooses to explore, with an unflinching eye, controversial, often taboo subjects such as prostitution, homosexuality, child rape, mental illness, pacifism, war, and murder by minors. Many readers come to Barker’s work through her best-known books, the Regeneration (1991–1995) trilogy, the third book of which won the Booker Prize in 1995. There is no doubt that Regeneration, with its attention to historical detail and skilful blending of factual and fictional characters is her most subtle and satisfying work. These novels have often been criticised as horrific, brutal, even brutish, yet only by getting close to the base, shocking, palpable detail of the First World War and the mental, as well as physical distress caused by close proximity to danger and death, can we better understand it. (contemporarywriters.com critical perspective)

Barnes, Julian, The History of the World in 10 1/2 Chapters

A revisionist view of Noah’s Ark, told by the stowaway woodworm. A chilling account of terrorists hijacking a cruise ship. A court case in 16th-century France in which the woodworm stand accused. A desperate woman’s attempt to escape radioactive fallout on a raft. An acute analysis of Gericault’s “Scene of Shipwreck.” The search of a 19th-century Englishwoman and of a contemporary American astronaut for Noah’s Ark. An actor’s increasingly desperate letters to his silent lover. A thoughtful meditation on the novelist’s responsibility regarding love. These and other stories make up Barnes’s witty and sometimes acerbic retelling of the history of the world. The stories are connected, if only tangentially, which is precisely Barnes’s point: historians may tell us that “there was a pattern,” but history is “just voices echoing in the dark; . . . strange links, impertinent connections.” Fascinating reading from the author of Flaubert’s Parrot, but not for those wanting conventional plot. (Library Journal review)

Barry, Sebastian, A Long Long Way

Willie Dunne is born in a storm during the “dying days” of Ireland. It is not an auspicious beginning. This novel of Ireland and World War I wears a cloak of gloom and doom as thick as the opening storm. Willie’s mother dies young. Willie enlists in the army and fights on the Western Front. Willie’s sweetheart marries another, and so on. The wartime scenes are brutally realistic. Throughout this dark novel, though, are glimpses of sweetness and light, such as a scene where Willie’s father bathes the returning soldier in an attempt to rid him of lice. Those not familiar with British-Irish history may find some of the personal conflicts and politics in the novel confusing, but nevertheless a compellingly sad, if difficult, read. (Booklist review)

Barth, John, The Last Voyage of Somebody the Sailor

Just when you may have concluded, like Queen Scheherazade’s husband, that you’ve “heard them all,” Barth (The Tidewater Tales) proves again how original and entertaining he is. Like many of the author’s previous works, his latest blends fantasy, mythology, existentialist wit, bawdy humor and metafictional conceits. But though his opening words declare, “The machinery’s rusty,” the new novel is a testament both to Barth’s undiminished generative powers and to his maturity of vision. In the elaborate plot, a “fifty-plus,” “once-sort-of-famous” New Journalist named Simon William Behler is mysteriously transported to the medieval Baghdad of Sindbad the Sailor. Behler–known variously as “Somebody the Sailor,” “Baylor” and “Sayyid Bey el-Loor,” falls in love with Sindbad’s daughter Yasmin and gets enmeshed in Arabian intrigues. The intrigues revolve around such nagging questions as the intactness of Yasmin’s virginity, the veracity of Sindbad’s tall tales and the whereabouts of a wristwatch Behler needs in order to return home. All this is dealt with in the course of six evenings of storytelling at Sindbad’s dinner table. Barth creates whole and engaging characters with his usual wealth of wordplay, allusion and satire. But the novel’s greatest achievement is how it connects the conventionally realistic story of Behler’s 20th-century life with the outsize and metaphorical world of Sindbad, reflecting in the process on the nature of stories, dreams, voyages and death. (Publishers Weekly review)

Byatt, A.S., The Children’s Book

Bristling with life and invention, The Children’s Book is a seductive work by an extraordinarily gifted writer. Set primarily in the downs and marshes of the Kent countryside and the southeastern coast at Dungeness, the story also flings characters to London, Paris, Munich, the Italian Alps and the battlefields of Europe, where real historical figures such as J.M. Barrie and Emma Goldman mix with invented characters including layabout students, Fabian socialists, potters, puppeteers, randy novelists and poets in the trenches of France. In its encyclopaedic form, The Children’s Book is a kind of anatomy of the age in which the young men and women of the Edwardian era were confronted by a rapidly changing society and the grim reality of the Great War. But more compelling than the social and political history is the domestic drama among the dozen or more characters that Byatt draws in vivid detail. (Washington Post review)

Carey, Peter, My Life as a Fake

Carey, who won the Man Booker Prize for his True History of the Kelly Gang, takes another strange but much less well-known episode in Australian history as the basis for this hypnotic novel of personal and artistic obsession. He tells it through the eyes of Lady Sarah Wode-Douglass, editor of a struggling but prestigious London poetry journal, who one day in the early 1970s finds herself accompanying an old family friend, poet and novelist John Slater, out to Malaysia. There they encounter an eccentric Australian expatriate, Christopher Chubb, who concocted, Slater says, a huge literary hoax in Australia just after the war, creating an imaginary genius poet, Bob McCorkle, whose publication by a little magazine led to the suicide of the magazine’s editor. Now Chubb offers Lady Sarah a page of poetry that shows undoubted genius and claims it is from a book in his possession. The tale is a tour de force, with a positively Graham Greene-ish relish in the seamy side of the tropics, a mix of literary detective story and murderous nightmare that is piquantly hair-raising. And just when it seems that Carey’s story is his greatest fantastic creation to date, he lets on that the hoax at the heart of it actually took place in Melbourne in 1946. As so often before, this extravagantly gifted writer has created something bewilderingly original and powerful. (Publishers Weekly review) (see my review at The Modern Word)

Catton, Eleanor, The Luminaries

Winner of the Man Booker Prize 2013. It is 1866, and Walter Moody has come to make his fortune upon the New Zealand goldfields. On arrival, he stumbles across a tense gathering of twelve local men, who have met in secret to discuss a series of unsolved crimes. A wealthy man has vanished, a whore has tried to end her life, and an enormous fortune has been discovered in the home of a luckless drunk. Moody is soon drawn into the mystery: a network of fates and fortunes that is as complex and exquisitely patterned as the night sky. The Luminaries is an extraordinary piece of fiction. It is full of narrative, linguistic and psychological pleasures, and has a fiendishly clever and original structuring device. Written in pitch-perfect historical register, richly evoking a mid-19th century world of shipping and banking and goldrush boom and bust, it is also a ghost story, and a gripping mystery. It is a thrilling achievement for someone still in her mid-20s, and will confirm for critics and readers that Catton is one of the brightest stars in the international writing firmament. (Amazon.com review)

Chabon, Michael, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay

Virtuoso Chabon takes intense delight in the practice of his art, and never has his joy been more palpable than in this funny and profound tale of exile, love, and magic. In his last novel, The Wonder Boys (1995), Chabon explored the shadow side of literary aspirations. Here he revels in the crass yet inventive and comforting world of comic-book superheroes, those masked men with mysterious powers who were born in the wake of the Great Depression and who carried their fans through the horrors of war with the guarantee that good always triumphs over evil. In a luxuriant narrative that is jubilant and purposeful, graceful and complex, hilarious and enrapturing, Chabon chronicles the fantastic adventures of two Jewish cousins, one American, one Czech. It’s 1939 and Brooklynite Sammy Klayman dreams of making it big in the nascent world of comic books. Joseph Kavalier has never seen a comic book, but he is an accomplished artist versed in the “autoliberation” techniques of his hero, Harry Houdini. He effects a great (and surreal) escape from the Nazis, arrives in New York, and joins forces with Sammy. They rapidly create the Escapist, the first of many superheroes emblematic of their temperaments and predicaments, and attain phenomenal success. But Joe, tormented by guilt and grief for his lost family, abruptly joins the navy, abandoning Sammy, their work, and his lover. As Chabon–equally adept at atmosphere, action, dialogue, and cultural commentary–whips up wildly imaginative escapades punctuated by schtick that rivals the best of Jewish comedians, he plumbs the depths of the human heart and celebrates the healing properties of escapism and the “genuine magic of art” with exuberance and wisdom. (Booklist review)

Chandra, Vikram, Red Earth and Pouring Rain

Setting 18th- and 19th-century Mogul India against the open highways of contemporary America and fusing Indian myth, Hindu gods, magic and mundane reality, this intricate first novel is a magnificent epic that welds the exfoliating storytelling style of A Thousand and One Nights to modernist fictional technique. Abhay, an Indian college student studying in the U.S. but home on vacation in Bombay, shoots a scavenging monkey; the dying creature reveals itself to be the reincarnation of Sanjay Parasher, a fiery, iconoclastic 19th-century poet and freedom-fighter against British rule. To remain alive, the monkey strikes a deal with the gods: he must keep Abhay’s family entertained each day by telling stories of his former lives. Around this fanciful premise, Indian novelist Chandra has built a powerful, moving saga that explores colonialism, death and suffering, ephemeral pleasure and the search for the meaning of life. Through the monkey’s tales, we learn of Sanjay’s lethal estrangement from his best friend, Sikander, an Anglo-Indian warrior who serves the British; of the suicide of Sikander’s mother, Janvi, who throws herself on a funeral pyre after her English husband gives away their daughters to missionaries; of Sanjay’s avenging showdown in London with Dr. Paul Sarthey, renowned orientalist and murderous imperialist. Abhay also narrates his own sprawling tale about his drive across the U.S. with two alienated fellow students, providing a dramatic contrast between America’s throwaway pop culture and India’s ancient, venerated ways, bound up with the concepts of dharma (right conduct), karma and reincarnation. This is an astonishing and brilliant debut. (Publishers Weekly review)

Clarke, Susanna, Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell

It’s 1808 and that Corsican upstart Napoleon is battering the English army and navy. Enter Mr. Norrell, a fusty but ambitious scholar from the Yorkshire countryside and the first practical magician in hundreds of years. What better way to demonstrate his revival of British magic than to change the course of the Napoleonic wars? Susanna Clarke’s ingenious first novel, Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell, has a cleverness and lightness of touch, but is less a fairy tale of good versus evil than a fantastic comedy of manners, complete with elaborate false footnotes, occasional period spellings, and a dense, lively mythology teeming beneath the narrative. Mr. Norrell moves to London to establish his influence in government circles, devising such powerful illusions as an 11-day blockade of French ports by English ships fabricated from rainwater. But however skillful his magic, his vanity provides an Achilles heel, and the differing ambitions of his more glamorous apprentice, Jonathan Strange, threaten to topple all that Mr. Norrell has achieved. A sparkling debut from Susanna Clarke–and it’s not all fairy dust. (Amazon.com review)

Coetzee, J.M., Waiting For the Barbarians

For decades the Magistrate has run the affairs of a tiny frontier settlement, ignoring the impending war between the barbarians and the Empire, whose servant he is. But when the interrogation experts arrive, he is jolted into sympathy with the victims and into a quixotic act of rebellion which lands him in prison, branded as an enemy of the state. Waiting for the Barbarians is an allegory of oppressor and oppressed. Not just a man living through a crisis of conscience in an obscure place in remote times, the Magistrate is an analogue of all men living in complicity with regimes that ignore justice and decency. (Publisher’s description)

Coupland, Douglas, Girlfriend in a Coma

After making love for the first time, high school senior Karen Ann McNeil confides to her boyfriend Richard of the dark visions she’s been recently suffering. It’s only a few hours later on that snowy Friday night in 1979 that she descends into a coma. Nine months later she gives birth to a daughter, Megan, her child by Richard, the protagonist of this disturbingly funny novel. Karen remains comatose for the next seventeen years. Richard and her circle of friends reside in an emotional purgatory throughout the next two decades; passing through careers as models, film special effects technicians, doctors, and demolition experts, before finally being reunited on a conspiracy-driven supernatural television series. Upon Karen’s reawakening, life grows as surreal as their television show. With apocalyptic events occurring, Karen, Richard, and their friends explore the essential mysteries of life, faith, decency, and existence. Amid the world’s rubble they attempt to restore their own humanity. (Publisher’s description)

Crace, Jim, Being Dead

Crace is a brilliant British writer whose novels are always varied in historical setting, voice, theme and writing style, and are surprising in content. This latest, sixth effort (after Quarantine), a stunning look at two people at the moment of their deaths, is the riskiest of his works, the most mesmerizing and the most deeply felt. Joseph and Celice, middle-aged doctors of zoology married to each other for almost 30 years, revisit the seaside where they first met and made love “in the singing salt dunes of Baritone Bay.” They are surprised on the dunes, murdered and robbed, and their bodies lie undiscovered for days. In alternating chapters of chronological counterpoint, Crace traces their last day, working backwards from the moment of their murders to their awakening that morning, innocent of what is to come. At the same time, he recreates the day they were introduced, in the 1970s, when they were researching their doctoral dissertations. In juxtaposing the remorselessness of nature against the hopes, desires and conflicted emotions of individuals, Crace gracefully integrates the facts and myths about the end of human life, and its transcendence (in Syl’s epiphanic vision), into a narrative of dazzling virtuosity. (Publishers Weekly review)

Crowley, John, Little, Big

John Crowley’s masterful Little, Big is the epic story of Smoky Barnable, an anonymous young man who travels by foot from the City to a place called Edgewood — not found on any map — to marry Daily Alice Drinkwater, as was prophesied. It is the story of four generations of a singular family, living in a house that is many houses on the magical border of an otherworld. It is a story of fantastic love and heartrending loss; of impossible things and unshakable destinies; and of the great Tale that envelops us all. It is a wonder. (Publisher’s description)

Danielewski, Mark, House of Leaves

When Johnny Truant attempts to organize the many fragments of a strange manuscript by a dead blind man, it gains possession of his very soul. The manuscript is a complex commentary on a documentary film (The Navidson Record) about a house that defies all the laws of physics. Navidson’s exploration of a seemingly endless, totally dark, and constantly changing labyrinth in the house becomes an examination of truth, perception, and darkness itself. The book interweaves the manuscript with over 400 footnotes to works real and imagined, thus illuminating both the text and Truant’s mental disintegration. First novelist Danielewski employs avant-garde page layouts that are occasionally a bit too clever but are generally highly effective. Although it may be consigned to the “horror” genre, this novel is also a psychological thriller, a quest, a literary hoax, a dark comedy, and a work of cultural criticism. It is simultaneously a highly literary work and an absolute hoot. This powerful and extremely original novel is strongly recommended. (Library Journal review)

DeLillo, Don, White Noise

Something is amiss in a small college town in Middle America. Something subliminal, something omnipresent, something hard to put your finger on. For example, teachers and students at the grade school are falling mysteriously ill: “Investigators said it could be the ventilating system, the paint or varnish, the foam insulation, the electrical insulation, the cafeteria food, the rays emitted by microcomputers, the asbestos fireproofing, the adhesive on shipping containers, the fumes from the chlorinated pool, or perhaps something deeper, finer-grained, more closely woven into the fabric of things.” J.A.K. Gladney, world-renowned as the living center, the absolute font, of Hitler Studies in North America in the mid-1980s, describes the malaise affecting his town in a superbly ironic and detached manner. But even he fails to mask his disquiet. There is menace in the air, and ultimately it is made manifest: a poisonous cloud–an “airborne toxic event”–unleashed by an industrial accident floats over the town, requiring evacuation. In the aftermath, as the residents adjust to new and blazingly brilliant sunsets, Gladney and his family must confront their own poses, night terrors, self-deceptions, and secrets. DeLillo is at his dark, hilarious best in this 1985 National Book Award winner, a novel that preceded but anticipated the explosion of the Internet, tabloid television, and the dialed-in, wired-up, endlessly accelerated tenor of the culture we live in. (Amazon.com review)

DeWitt, Helen, The Last Samurai

DeWitt’s ambitious, colossal debut novel tells the story of a young genius, his worldly alienation and his eccentric mother, Sibylla Newman, an American living in London after dropping out of Oxford. Her son, Ludovic (Ludo), the product of a one-night stand, could read English, French and Greek by the age of four. His incredible intellectual ability is matched only by his insatiable curiosity, and Sibylla attempts to guide her son’s education while scraping by on typing jobs. To avoid the cold, they ride the Underground on the Circle Line train daily, traveling around London as Ludo reads the Odyssey, learns Japanese and masters mathematics and science. Sybilla uses her favorite film, Akira Kurosawa’s classic Seven Samurai, as a makeshift guide for her son’s moral development. As Ludo matures and takes over the story’s narration, Sibylla is revealed as less than forthcoming on certain topics, most importantly the identity of Ludo’s father. Knowing only that his male parent is a travel writer, Ludo searches through volumes of adventure stories, but he is unsuccessful until he happens upon a folder containing his father’s name hidden in a sealed envelope. He arranges to meet the man, pretending to be a fan. The funny, bittersweet encounter ends with a gravely disappointed Ludo, unable to confront his father with his identity. Afterward, the sad 11-year-old resumes his search for his ideal parent figure. Using a test modeled after a scene in Seven Samurai, he seeks out five different men, claiming he is the son of each. While energetic and relentlessly unpredictable, the novel often becomes belabored with its own inventiveness, but the bizarre relationship between Sibylla and Ludo maintains its resonant, rich centrality, giving the book true emotional cohesion. (Publishers Weekly review)

Doctorow, E.L., Billy Bathgate

In the poorest part of the Bronx, in the depths of the Depression, a teenage, fatherless street kid who will adopt the name Billy Bathgate comes to the attention of his idol, master gangster Dutch Schultz. Resourceful, brash, daring and brave, the narrator understands that morality will have no influence in lifting him from his poverty; by hitching his wagon to the mobster’s star he can hope to provide his gentle, mad mother and himself with a way to rise out of their desolate existence. The astonishing story of Billy’s apprenticeship to Schultz and his education at the hands of the mobster’s minions is related by Doctorow with masterful skill, grace and lucidity of prose, inspired inventiveness of scene and true-voiced dialogue. Equally a rollicking adventure and a cautionary tale, both parable of the prodigal son and poignant coming-of-age story, it is mesmerizing reading that soars from the shocking first scene of a gangland execution through episodes of horror, hilarity and sudden, deepening insights. In this stunning, lyrical novel, Doctorow has perfected the narrative voice of a lower-class boy encountering the world. He falters only in a sentimental, almost fairytale ending that belies the harsh realities by which the narrative is propelled. But so fine and convincing is this story that the reader accepts in its entirety Doctorow’s mythical vision, a dark version of the Horatio Alger fable related with a brilliant twist. (Publishers Weekly review)

Dorst, Doug and J.J. Abrams., S.

One book. Two readers. A world of mystery, menace and desire. A young woman picks up a book left behind by a stranger. Inside it are his margin notes, which reveal a reader entranced by the story and by its mysterious author. She responds with notes of her own, leaving the book for the stranger, and so begins an unlikely conversation that plunges them both into the unknown. THE BOOK: Ship of Theseus, the final novel by a prolific but enigmatic writer named V. M. Straka, in which a man with no past is shanghaied onto a strange ship with a monstrous crew and launched on a disorienting and perilous journey. THE WRITER: Straka, the incendiary and secretive subject of one of the world’s greatest mysteries, a revolutionary about whom the world knows nothing apart from the words he wrote and the rumours that swirl around him. THE READERS: Jennifer and Eric, a college senior and a disgraced grad student, both facing crucial decisions about who they are, who they might become, and how much they’re willing to trust another person with their passions, hurts and fears. S., conceived by filmmaker J.J. Abrams and written by award-winning novelist Doug Dorst, is the chronicle of two readers finding each other in the margins of a book and enmeshing themselves in a deadly struggle between forces they don’t understand. It is also Abrams and Dorst’s love letter to the written word. (Publisher’s description)

Doyle, Roddy, Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha

In Roddy Doyle’s Booker Prize-winning novel Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha, an Irish lad named Paddy rampages through the streets of Barrytown with a pack of like-minded hooligans, playing cowboys and Indians, etching their names in wet concrete, and setting fires. Roddy Doyle has captured the sensations and speech patterns of preadolescents with consummate skill, and managed to do so without resorting to sentimentality. Paddy Clarke and his friends are not bad boys; they’re just a little bit restless. They’re always taking sides, bullying each other, and secretly wishing they didn’t have to. All they want is for something–anything–to happen. Throughout the novel, Paddy teeters on the nervous verge of adolescence. In one scene, Paddy tries to make his little brother’s hot water bottle explode, but gives up after stomping on it just one time: “I jumped on Sinbad’s bottle. Nothing happened. I didn’t do it again. Sometimes when nothing happened it was really getting ready to happen.” Paddy Clarke senses that his world is about to change forever–and not necessarily for the better. When he realizes that his parents’ marriage is falling apart, Paddy stays up all night listening, half-believing that his vigil will ward off further fighting. It doesn’t work, but it is sweet and sad that he believes it might. Paddy’s logic may be fuzzy, but his heart is in the right place. (Amazon.com review)

Duffy, Bruce, The World as I Found It

Vienna, 1900. The trenches of World War I and the dark slide into Nazi Europe. The intellectual lights of Cambridge University and the nabobs on the outskirts of Bloomsbury. Marriage and domestic life. These are just a few of the worlds the reader enters in this exhilarating novel of ideas, romance, and imagination. Irreverently trespassing on the turf of history, biography, and philosophy, The World as I Found It is the tale of three wildly different men adrift in the twentieth century. At the center is Ludwig Wittgenstein, one of the most magnetic philosophers of our time: brilliant, tortured, mercurial, forging his own solitary path while leaving a permanent mark-and sometimes a scar-on lives all around him. Playing in counterpoint are Wittgenstein’s two reluctant mentors: Bertrand Russell, past his philosophical prime yet eager to break new ground as a public intellectual, educational theorist, and sexual adventurer; and G. E. Moore, the great Cambridge don who exercised such an influence on E. M. Forster and who was devoted to the pleasures of the table and pure thought until, late in life, he discovered real fulfillment in marriage and fatherhood. By turns history, biography, and philosophy, The World as I Found It is the tale of three wildly different men adrift in the twentieth century: Ludwig Wittgenstein, Bertrand Russell, and G. E. Moore. Rich in humor and tragedy, lust and violence, spirit and striving, this is a novel that will enthrall any reader. (Publisher’s description)

Egan, Jennifer, A Visit From the Goon Squad

Jennifer Egan’s spellbinding novel circles the lives of Bennie Salazar, an aging former punk rocker and record executive, and Sasha, the passionate, troubled young woman he employs. Although Bennie and Sasha never discover each other’s pasts, the reader does, in intimate detail, along with the secret lives of a host of other characters whose paths intersect with theirs, over many years, in locales as varied as New York, San Francisco, Naples, and Africa. We first meet Sasha in her mid-thirties, on her therapist’s couch in New York City, confronting her longstanding compulsion to steal. Later, we learn the genesis of her turmoil when we see her as the child of a violent marriage, then a runaway living in Naples, then as a college student trying to avert the suicidal impulses of her best friend. We meet Bennie Salazar at the melancholy nadir of his adult life — divorced, struggling to connect with his nine-year-old son, listening to a washed up band in the basement of a suburban house — and then revisit him in 1979, at the height of his youth, shy and tender, reveling in San Francisco’s punk scene as he discovers his ardor for rock and roll and his gift for spotting talent. We learn what became of his high school gang — who thrived and who faltered — and we encounter Lou Kline, Bennie’s catastrophically careless mentor, along with the lovers and children left behind in the wake of Lou’s far flung sexual conquests and meteoric rise and fall. A Visit from the Goon Squad is a book about the interplay of time and music, about survival, about the stirrings and transformations set inexorably in motion by even the most passing conjunction of our fates. In a breathtaking array of styles and tones ranging from tragedy to satire to Powerpoint, Egan captures the undertow of self-destruction that we all must either master or succumb to; the basic human hunger for redemption; and the universal tendency to reach for both — and escape the merciless progress of time — in the transporting realms of art and music. Sly, startling, exhilarating work from one of our boldest writers. (Amazon.com review)

Eggers, Dave, What is the What

Valentino Achak Deng, real-life hero of this engrossing epic, was a refugee from the Sudanese civil war-the bloodbath before the current Darfur bloodbath-of the 1980s and 90s. In this fictionalised memoir, Eggers (A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius) makes him an icon of globalisation. Separated from his family when Arab militia destroy his village, Valentino joins thousands of other “Lost Boys,” beset by starvation, thirst and man-eating lions on their march to squalid refugee camps in Ethiopia and Kenya, where Valentino pieces together a new life. He eventually reaches America, but finds his quest for safety, community and fulfilment in many ways even more difficult there than in the camps: he recalls, for instance, being robbed, beaten and held captive in his Atlanta apartment. Eggers’s limpid prose gives Valentino an unaffected, compelling voice and makes his narrative by turns harrowing, funny, bleak and lyrical. The result is a horrific account of the Sudanese tragedy, but also an emblematic saga of modernity-of the search for home and self in a world of unending upheaval. (Publishers Weekly review)

Eugenides, Jeffrey, Middlesex

Eugenides’s second novel (after The Virgin Suicides) opens “I was born twice: first, as a baby girl…in January of 1960; and then again, as a teenage boy…in August of 1974.” Thus starts the epic tale of how Calliope Stephanides is transformed into Cal. Spanning three generations and two continents, the story winds from the small Greek village of Smyrna to the smoggy, crime-riddled streets of Detroit, past historical events, and through family secrets. The author’s eloquent writing captures the essence of Cal, a hermaphrodite, who sets out to discover himself by tracing the story of his family back to his grandparents. From the beginning, the reader is brought into a world rich in culture and history, as Eugenides extends his plot into forbidden territories with unique grace. His confidence in the story, combined with his sure prose, helps readers overcome their initial surprise and focus on the emotional revelation of the characters and beyond. Once again, Eugenides proves that he is not only a unique voice in modern literature but also well versed in the nature of the human heart. Highly recommended. (Library Journal review)

Ferris, Joshua, Then We Came to the End

In this wildly funny debut from former ad man Ferris, a group of copywriters and designers at a Chicago ad agency face layoffs at the end of the ’90s boom. Indignation rises over the rightful owner of a particularly coveted chair (“We felt deceived”). Gonzo e-mailer Tom Mota quotes Walt Whitman and Ralph Waldo Emerson in the midst of his tirades, desperately trying to retain a shred of integrity at a job that requires a ruthless attention to what will make people buy things. Jealousy toward the aloof and “inscrutable” middle manager Joe Pope spins out of control. Copywriter Chris Yop secretly returns to the office after he’s laid off to prove his worth. Rumors that supervisor Lynn Mason has breast cancer inspire blood lust, remorse, compassion. Ferris has the downward-spiraling office down cold, and his use of the narrative “we” brilliantly conveys the collective fear, pettiness, idiocy and also humanity of high-level office drones as anxiety rises to a fever pitch. Only once does Ferris shift from the first person plural (for an extended fugue on Lynn’s realization that she may be ill), and the perspective feels natural throughout. At once delightfully freakish and entirely credible, Ferris’s cast makes a real impression. (Publishers Weekly review)

Flanagan, Richard, The Narrow Road to the Deep North

A novel of the cruelty of war, and tenuousness of life and the impossibility of love. August, 1943. In the despair of a Japanese POW camp on the Thai-Burma death railway, Australian surgeon Dorrigo Evans is haunted by his love affair with his uncle’s young wife two years earlier. Struggling to save the men under his command from starvation, from cholera, from beatings, he receives a letter that will change his life forever. This savagely beautiful novel is a story about the many forms of love and death, of war and truth, as one man comes of age, prospers, only to discover all that he has lost. (Publisher’s description)

Fowler, Karen Joy, We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves

As a girl in Indiana, Rosemary, Fowler’s breathtakingly droll 22-year-old narrator, felt that she and Fern were not only sisters but also twins. So she was devastated when Fern disappeared. Then her older brother, Lowell, also vanished. Rosemary is now prolonging her college studies in California, unsure of what to make of her life. Enter tempestuous and sexy Harlow, a very dangerous friend who forces Rosemary to confront her past. We then learn that Rosemary’s father is a psychology professor, her mother a nonpracticing scientist, and Fern a chimpanzee. Fowler, author of the best-selling The Jane Austen Book Club (2004), vigorously and astutely explores the profound consequences of this unusual family configuration in sustained flashbacks. Smart and frolicsome Fern believes she is human, while Rosemary, unconsciously mirroring Fern, is instantly tagged “monkey girl” at school. Fern, Rosemary, and Lowell all end up traumatized after they are abruptly separated. As Rosemary — lonely, unmoored, and caustically funny — ponders the mutability of memories, the similarities and differences between the minds of humans and chimps, and the treatment of research animals, Fowler slowly and dramatically reveals Fern and Lowell’s heartbreaking yet instructive fates. Piquant humor, refulgent language, a canny plot rooted in real-life experiences, an irresistible narrator, threshing insights, and tender emotions — Fowler has outdone herself in this deeply inquisitive, cage-rattling novel. (Booklist review)

Frayn, Michael, Spies

By the author of the bestselling Booker Prize finalist Headlong, this dark, nostalgic and bittersweet parable evokes the childhood escapades of an isolated and hapless young boy caught up in the uncertainties of wartime London in the early 1940s, just after the horrors of the Luftwaffe blitz. Stephen Wheatley, now a grandfather living abroad, is drawn back to London to revisit his boyhood home, to deal with the complexities and eventual tragedy engendered by what seemed a harmless game of spy when he was just a schoolboy during WWII. His best friend at the time was Keith Hayward, the bright son of rather standoffish parents; Keith and Stephen embark on a childish adventure after Keith announces that his British mother is a German spy. The murky plot follows their frustrations as they try to shadow Keith’s mum as she goes through the mundane ritual of stopping by her sister’s house with letters and a shopping basket, only to disappear into the neighboring streets. Discovering at last that she takes a route through the culvert beneath the railroad and leaves letters in a box hidden on the other side, they eventually learn that she sometimes meets a tattered, bearded tramp hiding in a bombed-out cellar. When Keith’s mum finally realizes they have found her out, she secretly seeks Stephen’s loyalty, making him complicit. Thrust into a role far beyond his years, but helpless to refuse, he is overwhelmed. As it plays out to a surprising denouement, this enigmatic melodrama will keep readers’ attention firmly in hand. (Publishers Weekly review)

Gaiman, Neil, Anansi Boys

If readers found the Sandman series creator’s last novel, American Gods, hard to classify, they will be equally nonplussed — and equally entertained — by this brilliant mingling of the mundane and the fantastic. “Fat Charlie” Nancy leads a life of comfortable workaholism in London, with a stressful agenting job he doesn’t much like, and a pleasant fiancée, Rosie. When Charlie learns of the death of his estranged father in Florida, he attends the funeral and learns two facts that turn his well-ordered existence upside-down: that his father was a human form of Anansi, the African trickster god, and that he has a brother, Spider, who has inherited some of their father’s godlike abilities. Spider comes to visit Charlie and gets him fired from his job, steals his fiancée, and is instrumental in having him arrested for embezzlement and suspected of murder. When Charlie resorts to magic to get rid of Spider, who’s selfish and unthinking rather than evil, things begin to go very badly for just about everyone. Other characters — including Charlie’s malevolent boss, Grahame Coats (“an albino ferret in an expensive suit”), witches, police and some of the folk from American Gods — are expertly woven into Gaiman’s rich myth, which plays off the African folk tales in which Anansi stars. But it’s Gaiman’s focus on Charlie and Charlie’s attempts to return to normalcy that make the story so winning — along with gleeful, hurtling prose. (Publishers Weekly review)

Ghosh, Amitav, The Calcutta Chromosome: A Novel of Fevers, Delirium & Discovery

The Calcutta Chromosome is one of those books that’s marketed as a mainstream thriller even though it is an excellent science fiction novel (It won the prestigious Arthur C. Clarke Award). The main character is a man named Antar, whose job is to monitor a somewhat finicky computer that sorts through mountains of information. When the computer finds something it can’t catalog, it brings the item to Antar’s attention. A string of these seemingly random anomalies puts Antar on the trail of a man named Murugan, who disappeared in Calcutta in 1995 while searching for the truth behind the discovery of the cure for malaria. This search for Murugan leads, in turn, to the discovery of the Calcutta Chromosome, which can shift bits of personality from one person to another. That’s when things really get interesting. (Amazon.com review)

Gold, Glen David, Carter Beats the Devil

In Carter Beats the Devil, Glen David Gold subjects the past to the same wondrous transformations as the rabbit in a skilled illusionist’s hat. Gold’s debut novel opens with real-life magician Charles Carter executing a particularly grisly trick, using President Warren G. Harding as a volunteer. Shortly afterwards, Harding dies mysteriously in his San Francisco hotel room, and Carter is forced to flee the country. Or does he? It’s only the first of many misdirections in a magical performance by Gold. In the course of subsequent pages, Carter finds himself pursued by the most hapless of FBI agents; falls in love with a beautiful, outspoken blind woman; and confronts an old nemesis bent on destroying him. Throw in countless stunning (and historically accurate) illusions, some beautifully rendered period detail, and historical figures like young inventor Philo T. Farnsworth and self-made millionaire Francis “Borax” Smith, and you have old-fashioned entertainment executed with a decidedly modern sensibility. Gold has written for movies and TV, so it’s no surprise that he delivers snappy, fast-paced dialogue and action scenes as expertly scripted as anything that’s come out of Hollywood in years. Carter Beats the Devil has a mustachioed villain, chase scenes, a lion, miraculous escapes, even pirates, for God’s sake. Yet none of this is as broadly drawn as it might sound: Gold’s characters are driven by childhood sorrows and disappointments in love, just like the rest of us, and they’re limned in clever, quicksilver prose. By turns suspenseful, moving, and magical, this is the historical novel to give to anyone who complains that contemporary fiction has lost the ability to both move and entertain. (Amazon.com review)

Grass, Gunter, The Tin Drum

The greatest German novel since the end of World War II, The Tin Drum is the autobiography of Oskar Matzerath, thirty years old, detained in a mental hospital, convicted of a murder he did not commit. On the day of his third birthday, Oskar had “declared, resolved, and determined [to] stop right there, remain as I was, stay the same size, cling to the same attire” (striped pullover and patent-leather shoes). That same day Oskar receives his first tin drum, and from then on it is the means of his expression, allowing him to draw forth memories from the past as well as judgments about the horrors, injustices, and eccentricities he observes through the long nightmare of the Nazi era. As that era ebbs bloodily away, as drum succeeds drum, Oskar participates in the German postwar economic miracle — working variously in the black market, as an artist’s model, in a troupe of traveling musicians. With the onset of affluence and fame, Oskar decides to grow a few inches, only to develop a humpback. But despite his newfound status (and stature), Oskar remains haunted by the deaths of his parents, afflicted by his responsibility for past sins — and so assumes guilt for a murder he did not commit as an act of atonement and an opportunity to find consolation. The rhythms of Oskar’s drums are intricate and insistent, and they lead us, often by way of shocking fantasies, through the dark forest of German history. Through Oskar’s piercing, outspoken voice and deformed little figure, through the imaginative distortion and exaggeration of historical experience, a pathetically hilarious yet startlingly true portrayal of the human situation comes into view. (Publisher’s description)

Grenville, Kate, The Secret River

William Thornhill, a boatman in pre-Victorian London, escapes the harsh circumstances of his lower-class, hard-scrabble life and ends up a prosperous, albeit somehow unsatisfied, settler in Australia. After being caught stealing, he is sentenced to death; the sentence is commuted to transportation to Australia with his pregnant wife. Readers are filled with a sense of foreboding that turns out to be well founded. Life is difficult, but through hard work and initiative the Thornhills slowly get ahead. During his sentence, William has made his living hauling goods on the Hawkesbury River and thirsting after a piece of virgin soil that he regularly passes. Once he gains his freedom, his family moves onto the land, raises another rude hut, and plants corn. The small band of Aborigines camping nearby seems mildly threatening: William cannot communicate with them; they lead leisurely hunter/gatherer lives that contrast with his farming labor; and they appear and disappear eerily. They are also masterful spearmen, and Thornhill cannot even shoot a gun accurately. Other settlers on the river want to eliminate the Aborigines. The culture clash becomes violent, with the protagonist unwillingly drawn in. The characters are sympathetically and colorfully depicted, and the experiencing of circumstances beyond any single person’s control is beautifully shown. (School Library Journal review)

Haddon, Mark, The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time

Christopher Boone, the autistic 15-year-old narrator of this revelatory novel, relaxes by groaning and doing math problems in his head, eats red-but not yellow or brown-foods and screams when he is touched. Strange as he may seem, other people are far more of a conundrum to him, for he lacks the intuitive “theory of mind” by which most of us sense what’s going on in other people’s heads. When his neighbor’s poodle is killed and Christopher is falsely accused of the crime, he decides that he will take a page from Sherlock Holmes (one of his favorite characters) and track down the killer. As the mystery leads him to the secrets of his parents’ broken marriage and then into an odyssey to find his place in the world, he must fall back on deductive logic to navigate the emotional complexities of a social world that remains a closed book to him. Though Christopher insists, “This will not be a funny book. I cannot tell jokes because I do not understand them,” the novel brims with touching, ironic humor. The result is an eye-opening work in a unique and compelling literary voice. (Publishers Weekly review)

Harrison, M. John, Light

In M. John Harrison’s dangerously illuminating new novel, three quantum outlaws face a universe of their own creation, a universe where you make up the rules as you go along and break them just as fast, where there’s only one thing more mysterious than darkness. In contemporary London, Michael Kearney is a serial killer on the run from the entity that drives him to kill. He is seeking escape in a future that doesn’t yet exist — a quantum world that he and his physicist partner hope to access through a breach of time and space itself. In this future, Seria Mau Genlicher has already sacrificed her body to merge into the systems of her starship, the White Cat. But the “inhuman” K-ship captain has gone rogue, pirating the galaxy while playing cat and mouse with the authorities who made her what she is. In this future, Ed Chianese, a drifter and adventurer, has ridden dynaflow ships, run old alien mazes, surfed stellar envelopes. He “went deep” — and lived to tell about it. Once crazy for life, he’s now just a twink on New Venusport, addicted to the bizarre alternate realities found in the tanks — and in debt to all the wrong people. Haunting them all through this maze of menace and mystery is the shadowy presence of the Shrander — and three enigmatic clues left on the barren surface of an asteroid under an ocean of light known as the Kefahuchi Tract: a deserted spaceship, a pair of bone dice, and a human skeleton.(Publisher’s description)

Hartnett, Sonya, Of a Boy

Rarely is a sentence turned so well, a setting so remarkably established, and a plot so evenly polished as in this book. Immediately, in the preface, readers are confronted with a spellbinding scenario. Three children head down the footpath from their home in Australia to the ice-cream shop, and they are never seen again. In a neighboring town, nine-year-old Adrian is fearful of much, talented, perceptive, curious, a virtual outcast in his school, and an unhappy resident in his grandmother’s home. He notices the three children who move into a house across the road and wonders if they could possibly be the missing trio. Adrian subsequently meets the oldest girl, Nicole, in the park one afternoon as she cares for a dying bird. His suspicions of her identity are further aroused by her sly answers to his inquiries. A psychic reports that the missing children are located near water, and Nicole and Adrian take it upon themselves to find them. Tightly composed and ripe with symbolism, this complex book will offer opportunities for rich discussion. (School Library Journal review)

Hemon, Aleksander, The Lazarus Project

America has a richer literary landscape since Aleksandar Hemon, stranded in the United States in 1992 after war broke out in his native Sarajevo, adopted Chicago as his new home. He completed his first short story within three years of learning to write in English, and since then his work has appeared in The New Yorker, Esquire, and The Paris Review and in two acclaimed books, The Question of Bruno and Nowhere Man. In The Lazarus Project, his most ambitious and imaginative work yet, Hemon brings to life an epic narrative born from a historical event: the 1908 killing of Lazarus Averbuch, a 19-year-old Jewish immigrant who was shot dead by George Shippy, the chief of Chicago police, after being admitted into his home to deliver an important letter. The mystery of what really happened that day remains unsolved (Shippy claimed Averbuch was an anarchist with ill intent) and from this opening set piece Hemon springs a century ahead to tell the story of Vladimir Brik, a Bosnian-American writer living in Chicago who gets funding to travel to Eastern Europe and unearth what really happened. The Lazarus Project deftly weaves the two stories together, cross-cutting the aftermath of Lazarus’s death with Brik’s journey and the tales from his traveling partner, Rora, a Bosnian war photographer. And while the novel will remind readers of many great books before it–Ragtime, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, Everything Is Illuminated–it is a masterful literary adventure that manages to be grand in scope and intimate in detail. It’s an incredibly rewarding reading experience that’s not to be missed. (Amazon.com review)

Hensher, Philip, The Mulberry Empire

In 1839, about 50,000 British troops entered Afghanistan to replace the amir with someone more palatable to the Empire. In this fictionalized account, we meet Burnes, a British explorer who ventures into the capital city of Kabul and befriends the soon-to-be-ousted Amir Dost Mohammed Khan. Through no planning of his own, Burnes becomes an emissary for the British government and attempts to forge a relationship with Afghanistan. The novel switches between Afghanistan and England, and in addition to Burnes, the reader meets many other characters, among them Bella, the woman who falls for Burnes but won’t follow him on his exotic journeys; Charles Masson, a deserter of the English forces who one day finds himself in Kabul and who later plots the downfall of Burnes; and Vitkevich, Burnes’s Russian counterpart, who is attempting to double-cross the amir. Hensher, winner of the Somerset Maugham Award for Kitchen Venom, combines numerous characters, plot lines, locales, and time shifts to tell an incredibly complex saga of rulers, empires, politics, imperialism, and revolt. The past events of which he writes mirror the present and maybe the future, giving the book a timeless quality. This well-executed work will appeal to serious fans of historical fiction. (Library Journal review)

Hoban, Russell, Riddley Walker

‘Walker is my name and I am the same. Riddley Walker. Walking my riddels where ever theyve took me and walking them now on this paper the same. There aint that many sir prizes in life if you take noatis of every thing. Every time will have its happenings out and every place the same. Thats why I finely come to writing all this down. Thinking on what the idear of us myt be. Thinking on that thing whats in us lorn and loan and oansome.’ Composed in an English which has never been spoken and laced with a storytelling tradition that predates the written word, Riddley Walker is the world waiting for us at the bitter end of the nuclear road. It is desolate, dangerous and harrowing, and a modern masterpiece. (Publisher’s description)

Hornby, Nick, High Fidelity

It has been said often enough that baby boomers are a television generation, but High Fidelity reminds that in a way they are the record-album generation as well. This hilarious novel is obsessed with music; Hornby’s narrator is an early thirtysomething bloke who runs a London record store. He sells albums recorded the old-fashioned way–on vinyl–and is having a tough time making other transitions as well, specifically to adulthood. The book is in one sense a love story, both sweet and interesting; most entertaining, though, are the hilarious arguments over arcane matters of pop music. (Amazon.co.uk review)

Howrey, Meg, The Wanderers

In an age of space exploration, we search to find ourselves. In four years, aerospace giant Prime Space will put the first humans on Mars. Helen Kane, Yoshihiro Tanaka, and Sergei Kuznetsov must prove they’re the crew for the historic voyage by spending seventeen months in the most realistic simulation ever created. Constantly observed by Prime Space’s team of “Obbers,” Helen, Yoshi, and Sergei must appear ever in control. But as their surreal pantomime progresses, each soon realizes that the complications of inner space are no less fraught than those of outer space. The borders between what is real and unreal begin to blur, and each astronaut is forced to confront demons past and present, even as they struggle to navigate their increasingly claustrophobic quarters — and each other. Astonishingly imaginative, tenderly comedic, and unerringly wise, The Wanderers explores the differences between those who go and those who stay, telling a story about the desire behind all exploration: the longing for discovery and the great search to understand the human heart. (Publisher’s description)

Hulme, Keri, The Bone People

Powerful and visionary, Keri Hulme has written the great New Zealand novel of our times. The Bone People is the story of Kerewin, a despairing part-Maori artist who is convinced that her solitary life is the only way to face the world. Her cocoon is rudely blown away by the sudden arrival during a rainstorm of Simon, a mute six-year-old whose past seems to hold some terrible trauma. In his wake comes his foster-father Joe, a Maori factory worker with a nasty temper. The narrative unravels to reveal the truths that lie behind these three characters, and in so doing displays itself as a huge, ambitious work that tackles the clash between Maori and European characters in beautiful prose of a heartrending poignancy. (Publisher’s description)

Hyland, MJ, Carry Me Down

John Egan is a misfit, ‘a twelve-year old in the body of a grown man with the voice of a giant who insists on the ridiculous truth’. With an obsession for the Guinness Book of Records and faith in his ability to detect when adults are lying, John remains hopeful despite the unfortunate cards life deals him. During one year in John’s life, from his voice breaking, through the breaking-up of his home life, to the near collapse of his sanity, we witness the gradual unsticking of John’s mind, and the trouble that creates for him and his family. Set in early seventies Ireland, Carry Me Down is a deeply sympathetic take on one sad boyhood, told in gripping, and at times unsettling, prose. It plays out its tragic plot against a disarmingly familiar background and refuses to portray any of its lovingly drawn characters as easy heroes or villains. (Publisher’s description)

Ihimaera, Witi, The Whale Rider

A poetic blend of reality and myth provides a riveting tale of adventure and passion. An ancient whale ridden by a mystical man rises from the sea, the rider throwing spears that blossom like seeds into gifts of nature. One last spear “-flew across a thousand years. When it hit the earth, it did not change but waited for another hundred and fifty years to pass until it was needed.” It sprouts when Kahu, a girl child, is born to the eldest grandson of the chief of the Maori in Whangara, New Zealand. Koro Apirana is disgusted; he needs a male child to continue the line of descent in the tribe. The years that follow further harden his heart toward his great-granddaughter in spite of the bottomless love and respect she showers upon him. The child’s great-grandmother, the irreverent Nanny Flowers, proves to be the strength of this family; she nurtures the girl whom she knows holds the key to the future. The complex mixture of archetypal characters and cultural troubles make this novel appropriate for mature readers. This story, originally published in New Zealand in 1987, is the basis of the recently released film by the same name. It’s a tale rich in intense drama and sociological and cultural information. (School Library Journal review)

Irving, John, The World According to Garp

This is the life and times of T. S. Garp, the bastard son of Jenny Fields — a feminist leader ahead of her times. This is the life and death of a famous mother and her almost-famous son; theirs is a world of sexual extremes — even of sexual assassinations. It is a novel rich with “lunacy and sorrow”; yet the dark, violent events of the story do not undermine a comedy both ribald and robust. In more than thirty languages, in more than forty countries — with more than ten million copies in print — this novel provides almost cheerful, even hilarious evidence of its famous last line: “In the world according to Garp, we are all terminal cases.” (Publisher’s description)

Ishiguro, Kazuo, Never Let Me Go

Kathy, Ruth and Tommy were pupils at Hailsham — an idyllic establishment situated deep in the English countryside. The children there were tenderly sheltered from the outside world, brought up to believe they were special, and that their personal welfare was crucial. But for what reason were they really there? It is only years later that Kathy, now aged 31, finally allows herself to yield to the pull of memory. What unfolds is the haunting story of how Kathy, Ruth and Tommy, slowly come to face the truth about their seemingly happy childhoods — and about their futures. Never Let Me Go is a uniquely moving novel, charged throughout with a sense of the fragility of our lives. (Publisher’s description)

Jemisin, N.K., The Broken Earth Trilogy (The Fifth Season, The Obelisk Gate, The Stone Sky)

In the first volume of [the] trilogy, a fresh cataclysm besets a physically unstable world whose ruling society oppresses its most magically powerful inhabitants. The continent ironically known as the Stillness is riddled with fault lines and volcanoes and periodically suffers from Seasons, civilization-destroying tectonic catastrophes. It’s also occupied by a small population of orogenes, people with the ability to sense and manipulate thermal and kinetic energy. They can quiet earthquakes and quench volcanoes…but also touch them off. While they’re necessary, they’re also feared and frequently lynched. The “lucky” ones are recruited by the Fulcrum, where the brutal training hones their powers in the service of the Empire. The tragic trap of the orogene’s life is told through three linked narratives (the link is obvious fairly quickly): Damaya, a fierce, ambitious girl new to the Fulcrum; Syenite, an angry young woman ordered to breed with her bitter and frighteningly powerful mentor and who stumbles across secrets her masters never intended her to know; and Essun, searching for the husband who murdered her young son and ran away with her daughter mere hours before a Season tore a fiery rift across the Stillness. Jemisin (The Shadowed Sun, 2012, etc.) is utterly unflinching; she tackles racial and social politics which have obvious echoes in our own world while chronicling the painfully intimate struggle between the desire to survive at all costs and the need to maintain one’s personal integrity. Beneath the story’s fantastic trappings are incredibly real people who undergo intense, sadly believable pain. With every new work, Jemisin’s ability to build worlds and break hearts only grows. (Kirkus review)

Jennings, Kate, Moral Hazard

This short, self-assured novel by Australian-born Jennings (Snake) brilliantly depicts the complicated life of a working woman on Wall Street during the dot-com boom. Cath, a freelance writer in her 40s, is married to Bailey, who’s 25 years her senior. When he develops Alzheimer’s, she takes a speech-writing job at an investment bank to pay for his expensive medical care. Wry but realistic, and realizing her position in a rigid boys’ club hierarchy, she suppresses her liberal sensibility and defers to the chauvinists who dominate the firm, even cozying up to Horace, the company’s most Machiavellian executive. Cath’s Virgil through this hell is Mike, a cynical but gabby risk manager whose gossip and instruction illuminate the high-stakes office politics and dismal science of Wall Street. As Bailey deteriorates, in scene after heartbreaking scene, Cath finds unexpected succor “in the belly of the beast.” Jennings, herself a former Wall Street speechwriter, makes it clear that the mad math of high finance and the delusions of Alzheimer’s resemble one another: it’s a metaphor she exploits with dramatic consequences in this piercing novel, gleaming with facets of hard-won knowledge, polished by experience and a keen intelligence. An ideal subway read for smart working men and women, it masterfully documents the culture of economic and corporate arrogance, while never losing sight of the human cost of such hubris. (Publishers Weekly review)

Jones, Gwyneth, Life

The lives of biologist Anna Senoz; her husband, Spence; and their university friends intertwine as they evolve from idealistic students into adults with concerns that may affect their world. When Anna discovers a curious genetic trend with implications for the human sexual identity and gender relations, she finds herself a pariah among her colleagues. This latest novel from British author Jones (Divine Endurance) portrays a near future of commercial globalisation in which gender discrimination persists in subtle ways, forcing biology to find a way to fight back to equalise the sexes. Beautifully written and elegantly paced, this story conveys bold speculative concepts through intensely human characters. (Library Journal review)

Jones, Lloyd, Mister Pip

“You cannot pretend to read a book. Your eyes will give you away. So will your breathing. A person entranced by a book simply forgets to breathe. The house can catch alight and a reader deep in a book will not look up until the wallpaper is in flames.” It is Bougainville in 1991 — a small village on a lush tropical island in the South Pacific. Eighty-six days have passed since Matilda’s last day of school as, quietly, war is encroaching from the other end of the island. When the villagers’ safe, predictable lives come to a halt, Bougainville’s children are surprised to find the island’s only white man, a recluse, re-opening the school. Pop Eye, aka Mr Watts, explains he will introduce the children to Mr Dickens. Matilda and the others think a foreigner is coming to the island and prepare a list of much needed items. They are shocked to discover their acquaintance with Mr Dickens will be through Mr Watts’ inspiring reading of Great Expectations. But on an island at war, the power of fiction has dangerous consequences. Imagination and beliefs are challenged by guns. Mister Pip is an unforgettable tale of survival by story; a dazzling piece of writing that lives long in the mind after the last page is finished. (Publisher’s description)

Kunzru, Hari, Transmission

Transmission is Hari Kunzru’s second novel and, in a similar vein to Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections, the title is instructive; it’s figuratively and literally, the book’s pulsing leitmotif. To transmit is, by definition, to “send across”, and the migration of information and people, the destruction and the erection of borders in our hi-tech, supposedly global village, (a world where Indian graduates gain Australian accents working in local call centres) is what this novel is all about. Leaving aside the broader forces of globalisation, Kunzru’s chief dramatic agent is a computer virus that meshes together the lives of his main characters: Arjun Mehta, a sexually-naïve Indian programmer working in America who unleashes the contagion; Leela Zahir, a Bollywood actress whose image the bug zooms across the globe and Guy Swift, head of Tomorrow, a Shoreditch-based consultancy whose ongoing quest to harness the “emotional magma that wells from the core of planet brand”, becomes somewhat nobbled in the immediate technological fallout. Of his cast, not unsurprisingly Guy comes closest to caricature (though his scheme to rebrand European border police as Ministry of Sound-style nightclub bouncers–”Europe: No Jeans, No Trainers”–sounds alarming believable). But then Guy’s is the incarnate of the worst, Panglossian traits of the West in this callow information age. His certainty and self-absorbed fecklessness (which thankfully he does eventually suffer, horribly for) contrasts jarringly with poor, Mehta, whose American dreams tip, all too swiftly into nightmare. (Amazon.co.uk review)

Kureishi, Hanif, The Black Album

Again cleverly mining the chaos and contradictions of multicultural, postmodern England, Kureishi (The Buddha of Suburbia) follows the turbulent social and spiritual education of an impressionable young Pakistani at an inferior London college, where he struggles with conflicting personal, familial and cultural allegiances. The year is 1989, and the publication of Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses has caused an international controversy. Shahid Hasan has left his bourgeois family in Kent to study in the city. As he falls in with a group of crusading young Muslims whose charismatic leader lives next door, Shahid also becomes deeply involved — both intellectually and sexually — with his liberal, humanistic professor Deedee Osgood, who has assigned him a term paper on the rock icon then known as Prince. Irresolute to the point of spinelessness, Shahid allows his beliefs to vacillate until a violent confrontation erupts. Kureishi insightfully probes issues of faith and individualism against a memorable landscape of urban and academic upheaval. While Shahid’s lack of conviction and personal loyalty make him a less than likable protagonist, there is ample fervor in the colorful supporting cast, and the author’s wit and considerable narrative talents easily embroil the reader in the novel’s unfolding drama. (Publishers Weekly review)

Lahiri, Jhumpa, The Namesake

Any talk of The Namesake–Jhumpa Lahiri’s follow-up to her Pulitzer Prize-winning debut, Interpreter of Maladies–must begin with a name: Gogol Ganguli. Born to an Indian academic and his wife, Gogol is afflicted from birth with a name that is neither Indian nor American nor even really a first name at all. He is given the name by his father who, before he came to America to study at MIT, was almost killed in a train wreck in India. Rescuers caught sight of the volume of Nikolai Gogol’s short stories that he held, and hauled him from the train. Ashoke gives his American-born son the name as a kind of placeholder, and the awkward thing sticks. Awkwardness is Gogol’s birthright. He grows up a bright American boy, goes to Yale, has pretty girlfriends, becomes a successful architect, but like many second-generation immigrants, he can never quite find his place in the world. There’s a lovely section where he dates a wealthy, cultured young Manhattan woman who lives with her charming parents. They fold Gogol into their easy, elegant life, but even here he can find no peace and he breaks off the relationship. His mother finally sets him up on a blind date with the daughter of a Bengali friend, and Gogol thinks he has found his match. Moushumi, like Gogol, is at odds with the Indian-American world she inhabits. She has found, however, a circuitous escape: “At Brown, her rebellion had been academic … she’d pursued a double major in French. Immersing herself in a third language, a third culture, had been her refuge–she approached French, unlike things American or Indian, without guilt, or misgiving, or expectation of any kind.” Lahiri documents these quiet rebellions and random longings with great sensitivity. There’s no cleverness or showing-off in The Namesake, just beautifully confident storytelling. Gogol’s story is neither comedy nor tragedy; it’s simply that ordinary, hard-to-get-down-on-paper commodity: real life. (Amazon.com review)

LeGuin, Ursula, The Dispossessed

Most of Le Guin’s science fiction is set in a human galaxy where the distance of time and space imposed by relativity is mitigated by instantaneous transmission of information through a gadget called the ansible. The Dispossessed was the book in which she told us of Shevek, the ansible’s inventor, and the ironies of his career. Shevek is a loyal citizen of a poor anarchist world, Anarres, which finds frills like research hard to afford; he travels to the neighbouring world of Urras, to find that unbridled capitalism is not much fun either. “Nio Esseia, a city of four million souls, lifted its delicate glittering towers across the green marshes of the Estuary as if it were built of mist and sunlight…Was all Nio Esseia this? Huge shining boxes of stone and glass, immense, ornate, enormous packages, empty, empty.” At once one of the greatest of SF novels about political ideas and idealism, and a stunning novel of character, The Dispossessed has at its centre Shevek, scientist and near-saint, a flawed human being whom we come to know as we know few characters in modern science fiction. (Amazon.co.uk review)

Leigh, Julia, The Hunter

The young Australian writer, Julia Leigh, has been hailed as a talent to watch in the 21st century. The Hunter, her first novel, is a strange and haunting story which opens straight onto the world of its protagonist, M: “The mini-bus takes fifteen minutes to arrive in town: “Welcome to Tiger Town” reads a sign by the highway, “Population: 20,000″”. Assuming the identity of Martin David, Naturalist, M makes his preparations for a hunt: he, and the reader, will be spending some time in the Tasmanian wilderness in search of the legendary tiger, the thylacine. In crafted, measured and often beautiful prose, Leigh offers her readers glimpses of who M is, or might be, and what he is looking for. There is a hint that the thylacine’s genetic material has been “declared capable of winning a thousand wars”, a gift to bio-weaponry, but M remains detached: “M does not know, cannot know and does not want to know, but there is no question the race is on to harvest the beast”. M’s not wanting to know guides the narrative: he is solitary, unconnected, only occasionally giving in to the desires for human and sexual, contact which emerge through M’s vague, yet somehow yearning, association with the woman and two children with whom he stays when not out on the hunt. But the feeling centre of the book is anchored elsewhere in the unique connection between M and the tiger, in Leigh’s meticulous exploration of the beauty–and terror–of the relation between killer and killed. (Amazon.co.uk review)

Lethem, Jonathan, The Fortress of Solitude